War Powers Resolution Reporting:

Presidential Practice and the Use of Armed Forces Abroad, 1973-2019

January 2020

Introduction

In an era of U.S. military engagement across the globe, the roles and responsibilities of Congress and the President in deciding when and how our armed forces are used remain deeply contested. The Constitution provides the majority of war powers to Congress, but over many decades of practice the executive branch has steadily accreted power to act without congressional authorization—and sometimes without congressional knowledge. And in recent decades, the courts have declined to resolve related disputes. Congress’ primary mechanism for addressing this imbalance is a 45-year-old statute known as the War Powers Resolution (WPR). The record under the WPR is mixed: On one hand, many of its provisions are insufficient to serve the purpose for which they were intended or have been stripped of their utility in practice; on the other hand, Presidents have, for the most part, adhered to the requirements to report use of our military abroad to Congress as the statute requires, although the information reported is often ambiguous and sometimes incomplete. The quality of the transparency created by these reports is key to the proper functioning of the WPR framework as a whole.

This project systematically analyzes four and a half decades of presidential notifications to Congress, yielding a wealth of data that helps us understand how the WPR’s transparency-forcing reporting mechanism is working in practice. The analysis drawn from that data elucidates how Presidents engage our armed forces abroad, the quality of information Congress has in order to fulfill its constitutional role, and the gaps and shortcomings that could be addressed to strengthen the WPR’s existing reporting framework.

More generally, this project offers insight into the deployment of U.S. armed forces across the globe and across different presidential administrations over time—a subject of broad significance for experts and the public writ large.

The Constitutional Framework

Article II of the U.S. Constitution designates the President as commander in chief of the armed forces, but Article I grants Congress the power to “declare war,” along with a number of other war-related powers that were vitally important at the time of our founding in regulating whether and how the nation would become involved in armed conflict.1 Congress was given the authority to decide whether the nation should go to war because of, not in spite of, its slower pace of action compared with the speed of the executive branch. This design “is a feature, not a bug”—it “anticipates that Congress would be less inclined to go to war” than the President.2

While the framers of our Constitution believed it was Congress’ responsibility to authorize the use of our armed forces, an implicit, narrow exception has long been recognized for emergency cases in which presidential action was required to repel a sudden armed attack.3 Over time, however, the executive branch has articulated a much wider, and remarkably malleable, test for unilateral presidential action:

Today, whether or not the president can launch the country into a conflict without congressional approval starts with a much broader question than “Is the nation in immediate peril?” Rather, the executive branch has framed the extent of the president’s Article II authority to use the nation’s armed forces abroad in terms of a two-part test: first, whether there is a sufficient “national interest” to justify the use of force, and second, whether the anticipated “nature, scope and duration” of military action would take the country into “war in the constitutional sense.”4

The requirement that the President assert an important “national interest” has been “interpreted so broadly over time that it imposes few meaningful limits on the presidency.”5 Indeed, following decades of expansion beyond the core historical cases of unilateral presidential action to repel attacks on the United States, or to protect U.S. nationals abroad,6 it can be difficult to discern a limiting principle that would provide an outer boundary to the types of “national interests” that would satisfy this test in the view of the executive branch.

The second aspect of this test is somewhat more confining, but still quite broad: To constitute “war” in the “constitutional sense,” and thus constrain the President from acting without congressional authorization, the executive branch analysis generally requires “prolonged and substantial military engagements, typically involving exposure of U.S. military personnel to significant risk over a substantial period.”7 Activity far short of that description can make the United States party to an armed conflict, raise the prospect of escalation, or have significant political consequences.

The War Powers Resolution

What means does Congress have at its disposal to regulate unilateral presidential deployments of our armed forces? Its primary mechanism for forcing transparency on the part of the President and asserting its own constitutional role remains the War Powers Resolution of 1973 (WPR).8 The landmark statute was passed over President Nixon’s veto, following the calamitous U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, which had begun with unilateral presidential deployments of military “advisors” (prior to the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which was subsequently used as broad statutory authorization for the war), and included a secret bombing campaign in Cambodia hidden even from Congress.

The WPR created a set of procedures intended to help reset the balance of power between the political branches in matters of war and peace. It did so by ensuring the nation would not be brought into situations that could lead to armed conflict without at least congressional knowledge, and crucially, by providing a mechanism for Congress to terminate involvement in hostilities with a simple majority of both chambers (although that mechanism was subsequently rendered far less powerful, as discussed below).9

The reporting requirements in section 4(a) of the WPR, which are the subject of this project, are the WPR’s core means of providing transparency and ensuring Congress has the necessary information to make decisions regarding how the nation’s armed forces are used abroad.10 They require the President to notify Congress “in the absence of a declaration of war” whenever U.S. armed forces are introduced: “(1) into hostilities or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances; (2) into the territory, airspace or waters of a foreign nation, while equipped for combat,” with a few limited exceptions; “or (3) in numbers which substantially enlarge United States Armed Forces equipped for combat already located in a foreign nation.”11 These reports must be submitted within 48 hours of any of the triggering events in section 4(a), and are thus widely referred to as “48-hour reports.”12

While all three triggers for 48-hour reporting inform Congress that the President has taken a significant action involving the use of U.S. armed forces abroad, reports under section 4(a)(1) are particularly important: Only reports issued under that section are linked to the key mechanism in the WPR intended to provide teeth to Congress’ ability to prevent the President from initiating unauthorized conflicts. Specifically, section 4(a)(1) reports trigger a 60-day clock (extendable to 90 days under certain circumstances) that requires the President to cease the use of armed forces if Congress has not authorized continued engagement.13 The clock begins when Congress is notified of the activity through a section 4(a)(1) report, or within 60 days of when a report under section 4(a)(1) was supposed to be submitted, whichever is earlier.

What Purpose Does the War Powers Resolution Serve Today?

Forty-five years after its passage, the framework Congress envisaged in 1973 has been eroded by a number of factors. First, narrow interpretations of the statute by the executive branch, including the crucial term “hostilities,” have limited its reach in practice.14 This has been coupled in recent decades with expansive executive branch interpretations of existing authorizations for the use of force that Congress has previously granted.

Questions regarding the constitutionality of some of the WPR’s provisions have also dampened its power. Most Presidents, from Nixon onward, have argued that the provision allowing Congress to terminate presidential use of armed forces in hostilities through passage of a joint resolution by simple majority of each chamber, without presentment to the President for signature or veto, violates Article I § 7 of the Constitution.15 That argument was strengthened after the Supreme Court struck down the “legislative veto” in an unrelated 1983 opinion,16 effectively eviscerating the WPR’s core concurrent resolution mechanism for reigning in unilateral presidential use of force abroad.

Some administrations have also argued that the requirement to terminate the use of armed forces at the conclusion of the 60- (or 90-) day clock is an infringement on presidential power,17 at least as applied to certain situations, although other administrations have explicitly recognized that “Congress may, as a general constitutional matter, place a 60-day limit on the use of our armed forces as required by the provisions” of the WPR.18 But also starting with the Nixon Administration, Presidents have not taken issue with the WPR’s reporting provisions,19 with which all Presidents following Nixon appear to have largely complied.

In addition, the WPR’s power to constrain unilateral presidential action has been outstripped in some respects by modern geopolitics and the changing nature of military operations. Hostile cyber operations, for example, can be conducted remotely, without introducing forces into foreign territory, and without crossing the threshold of the executive branch’s narrow definition of “hostilities” for WPR purposes. Other types of remote operations (such as those using remotely piloted drones) and common uses of our armed forces in missions alongside partners (including many “advise and assist” missions or the provision of logistical support) and in low-intensity conflict settings can likewise steer clear of the WPR’s triggers as interpreted by the executive branch, even if they bring the United States into situations of armed conflict or run the risk of doing so.

Nevertheless, the WPR remains the key statutory framework for regulating the relationship between the political branches with respect to the use of U.S. armed forces abroad. And while its termination provisions have not fulfilled the role that the post-Vietnam Congress imagined, Presidents continue to submit 48-hour reports.

To evaluate criticisms of the WPR, understand in what ways it may have succeeded, and build toward improvements in the future, experts and the general public would benefit from a more comprehensive understanding of how the statute has worked in practice. Do the WPR’s notification requirements provide sufficient information to Congress to ensure it can fulfill its constitutional role? If not, in what ways do these requirements come up short? What can we learn about how and why Presidents are using our armed forces abroad—often relying on their constitutional authority alone—by analyzing trends in reporting over the last four and a half decades?

To address these and other questions, this project creates a publicly accessible, searchable database analyzing the contents of all unclassified 48-hour reports submitted to Congress under the WPR since its passage, through December 31, 2019 and to be updated over time. Drawing from this data set, key initial findings, trends, and notable features of contemporary practice are highlighted here. It is our hope that answering fundamental questions about how the WPR’s notification procedures have been used in practice can lay the foundation for understanding what reforms may be needed to ensure the WPR can better serve its aims in the future.

Methodology

Detailed information about how the project data were collected and analyzed is contained in the methodology section.

Key Findings and Analysis

Analysis of the 105 48-hour reports filed as of December 31, 2019 provides a rich picture of how and why Presidents used armed forces abroad as reported to Congress under the WPR, their understanding of the constitutional authority for doing so (bolstered by statutory authority on a handful of important occasions representing initiation of major conflicts), the sufficiency of the War Powers Resolution’s notification requirements, as well as key deficiencies in the reporting framework. The database also provides a host of information that is not required to be reported under the terms of the statute, but that Presidents have nevertheless often included in describing reportable activity to Congress, such as the basis for the action under international law and whether the action was undertaken unilaterally or in coalition with other nations or organizations. In addition, the data illuminate trends in the nature of reportable activity, the types of enemies or risks to U.S. interests that armed forces address, and changes in these trends over time.

A Snapshot of the Dataset

The 105 reports span from President Ford’s April 4, 1975, notification of the use of U.S. forces to transport refugees in South Vietnam to safer areas in the country, to the November 11, 2019, report in which President Trump notified Congress of the deployment of additional forces to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to “assure our partners, deter further Iranian provocative behavior, and bolster regional defensive capabilities.”35

Number of Reports

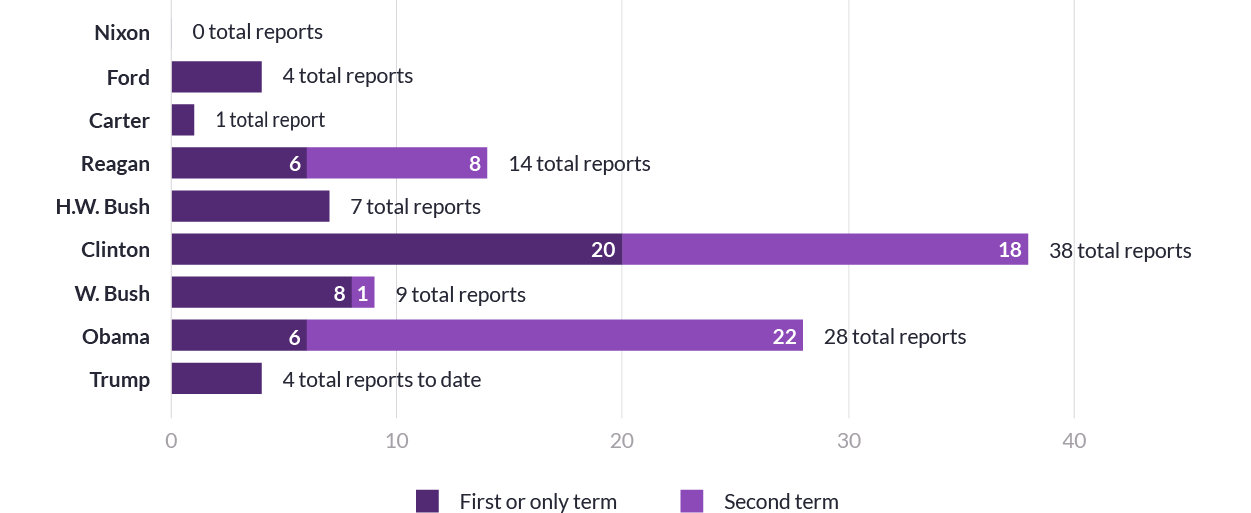

The number of reports filed by each President since the WPR’s enactment is shown in the chart below, separated by presidential term. President Nixon, over whose veto the WPR was enacted, did not file a single report. President Carter filed only one report, notifying Congress of the aborted attempt to rescue American hostages held at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. The highest number of reports per term were filed in President Obama’s second term (22) and President Clinton’s first term (20).

It is important to note, however, that not all reports are of equal significance. Some may notify Congress of a deployment or introduction into hostilities with great geopolitical, strategic, or humanitarian importance—others do not. Some have meaningful implications for the balance of powers between Congress and the President due to the nature of the activity and the claimed authority for engaging in the use of force, while others rest solidly on the authority of both political branches.

For these reasons, a higher number of reports in a given presidential term does not necessarily equate to a higher incidence of committing U.S. armed forces in situations that could lead to conflict. For example, President Reagan submitted only eight reports in his second term, but all involved an introduction into hostilities or imminent hostilities in which force was used against state actors.36 Moreover, combat-equipped introductions and substantial enlargements that do not report involvement in hostilities—which comprise 66 of the 105 reports—can be undertaken for any number of reasons, not necessarily for reasons that would lead to greater conflict. Indeed, reports spanning all of the purpose/mission categories are included in those 66 reports.

More reports can also mean a greater commitment to transparency. Given a major purpose of the WPR reporting framework is to ensure Congress is aware of deployments of U.S. armed forces into even non-hostile situations that could lead to situations involving hostilities in the future, providing reports in arguably borderline cases would be consistent with the spirit of the WPR, whereas providing fewer reports in borderline cases could be seen to undermine one of the statute’s core purposes.

Which WPR Reporting Requirement Triggered Notification

As described above, 48-hour reports are required in three circumstances: when Presidents introduce forces into hostilities or imminent hostilities, deploy combat-equipped forces, or substantially enlarge a combat-equipped contingent. Of the 105 reports in this dataset, 38 are coded as having been triggered by hostilities or imminent involvement in hostilities, 56 include a combat-equipped introduction into foreign territory, 21 include a substantial enlargement of a combat-equipped force, and only one was coded as having an unknown reporting trigger based on the information provided in the report.37 Further analysis of the reports based on which of these reporting requirements triggered the notification is provided below.

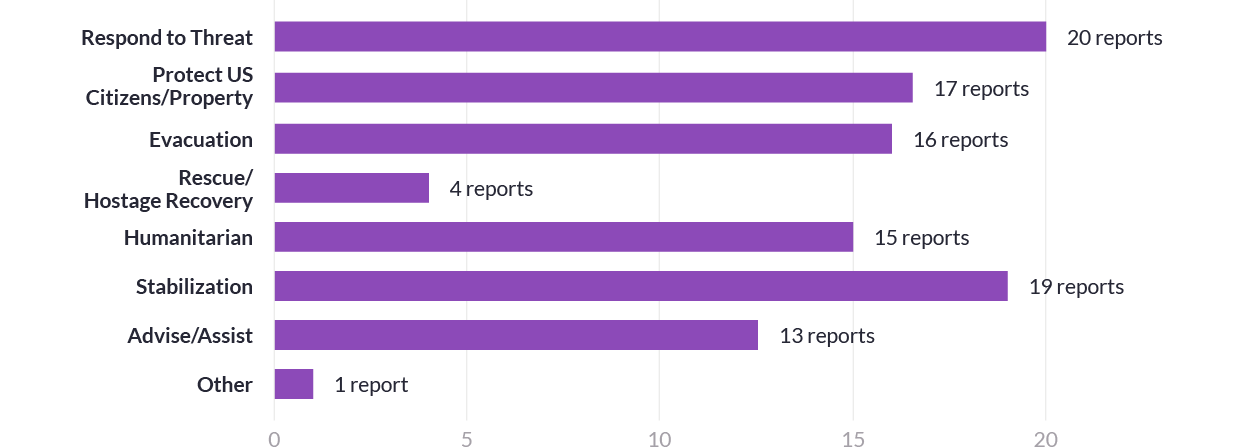

Reported Purpose of Activity

The dataset also provides a snapshot of the purposes for which Presidents report introducing U.S. armed forces abroad. As shown in Figure 2, 37 of the reports were coded as notifying Congress of an introduction or deployment of U.S. forces to protect U.S. citizens or property, conduct an evacuation, or undertake a rescue or hostage recovery operation. Of these, the vast majority (33) are related to evacuations or protecting U.S. citizens or property, often in situations of violent unrest or significant political uncertainty. Rescues and hostage recoveries comprise a small subset of this group, with only four reports. As expected given the urgent nature of these types of missions, none of the 37 rely on statutory authorization by Congress and very few (only two) involve joint or coalition forces. While unilateral and undertaken solely pursuant to the President’s claimed Article II authority, few were coded as involving hostilities or imminent involvement in hostilities (five reports of the 37). Moreover, several explicitly disclaim any intention to impact the political situation in the country at issue.38

Forty-seven of the 48-hour reports in the dataset—roughly half—are coded as humanitarian, stabilization missions, or missions to advise or assist partner organizations or forces.39 Of these, the data reveals that nearly all (45) are joint or coalition missions, which is again unsurprising given the nature of the reported activity. Presidents reported consent of the territorial state or UN Security Council authorization in 38 of these 47 cases (none of the 47 reports cite a claim of self-defense). While these deployments are less often undertaken unilaterally and the reports to Congress frequently invoke an international legal basis, they more often involve hostilities or imminent hostilities (17 of the 47) than the reports in the evacuations, protection of U.S. citizens or property, and rescue or hostage recovery categories.

Finally, 20 of the 105 reports in the dataset are coded as describing a response to a threat. The data also separately capture whether that threat emanated from a state or non-state actor (or both, as in one report by President W. Bush describing the beginning of combat operations in Afghanistan on October 9, 2001). These reports are further analyzed in Figure 3.

Changing Nature of Types of Threats to Which Presidents Are Responding

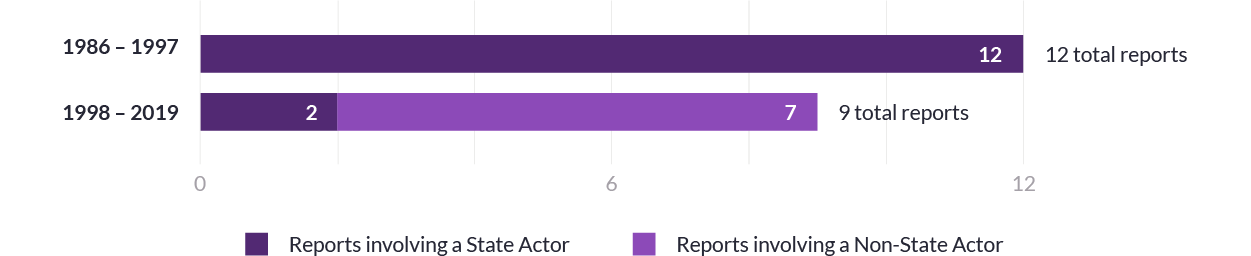

The use of armed forces abroad to respond to threats has shifted significantly from responding to state actors to responding to terrorist organizations.

As noted above, 20 of the 105 reports were coded as responding to a threat. These reports span from 1986 to 2016. Further breaking down this subset of reports by the “type of enemy” coded, we see a significant shift over time. Specifically, the dataset shows that the types of threats Presidents report responding to have shifted from involving primarily state actors in the Middle East and North Africa region to primarily non-state actors (terrorist organizations), generally in the same region.

The first 12 reports in the “respond to threat” category, from 1986 to 1998, exclusively involve threats from state actors. Moreover, those reports involve only three states: Libya (two reports by President Reagan in 1986); Iran (six reports by President Reagan involving the “Tanker Wars” of 1987–88); and Iraq (four reports by Presidents H.W. Bush and Clinton spanning from 1990–93).

The data present a turning point in 1998, when President Clinton informed Congress of strikes in Afghanistan and Sudan in response to the threat from a non-state actor: “the Usama bin Ladin organization.”40 The next report coded as a response to a threat describes operations in Yemen in October 2000 in response to the bombing of the USS Cole (perpetrated by al-Qaida).41 Indeed, from 1998 to the present, only two reports in the “response to threat” category are coded as involving state actors: President W. Bush’s October 9, 2001, report on the beginning of “combat action in Afghanistan against Al Qaida terrorists and their Taliban supporters” (comprising both a non-state and state actor, respectively), and his March 21, 2003, report on the invasion of Iraq. Moreover, of the post-1998 reports involving responding to threats by non-state actors, all but one of the reported threats are terrorist organizations.42

This significant shift is, if anything, an underrepresentation of the dramatic swing toward operations involving non-state actors in the post-9/11 era, given most of the activity authorized by the 2001 AUMF (covered only in periodic WPR reports under section 4(c), as explained above), is also directed against non-state terrorist organizations.

Rescue or hostage recovery operations follow a similar pattern, although the overall number of reports is much smaller. Of the four reports in this category, two in 1975 and 1980 involve attempts to rescue nationals from state actors (Cambodia and Iran). The two later reports, in 2012 and 2014, involve rescues from the hands of non-state actors—al-Shabaab and Boko Haram—both under President Obama.

Claimed Domestic Authority

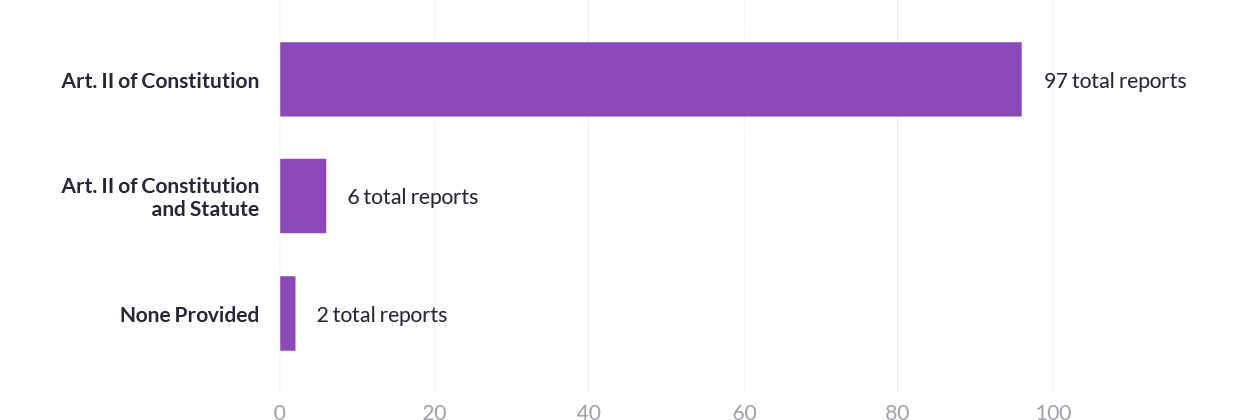

Presidents almost always rely solely on claimed Article II authority for WPR-reported activity, but major conflicts also involve congressional authorization.

In the overwhelming majority of the reports in this dataset—97 out of 105—the President notifies Congress that he is using armed forces pursuant to his authority under Article II of the Constitution alone. Only six reports also rely on statutory authority in combination with claimed Article II authority, and none rely on statutory authority alone. Two reports cite no domestic legal authority at all, as shown in the chart below.

This reliance on claimed Article II authority is, in some respects, unsurprising given a significant amount of military activity undertaken pursuant to congressional authorization is, according to the executive branch, only required to be included in periodic reports, as explained above. Indeed, activity purportedly undertaken pursuant to statutory authority has grown exponentially in the past two decades, as operations under the 2001 AUMF in particular have come to span vast geographic areas and involve the United States in a range of conflict settings, from Iraq and Afghanistan to Yemen and Somalia, and beyond, and involve armed groups that did not even exist at the time of the 2001 AUMF’s passage.43 As noted above, it is also unsurprising that reports of evacuations and embassy protection missions, for example, cite no statutory authority, as they are often undertaken urgently to protect nationals abroad.

Nevertheless, these data capture a significant finding along a different dimension: The initiation of each major war since Vietnam has involved a combination of congressional authorization and the President’s constitutional authority. As reported by President H.W. Bush, the 1991 Gulf War to dislodge Iraq from its occupation of Kuwait relied on a statutory force authorization, as well as Article II authority.44 Likewise, the 2003 invasion of Iraq reported by President W. Bush also cited both constitutional and statutory authority.45 Notably, President W. Bush’s September 24, 2001 report notifying Congress of the “Deployment of Forces in Response to the Terrorist Attacks of September 11” states that the actions are undertaken “pursuant to my constitutional authority to conduct U.S. foreign relations and as Commander in Chief and Chief Executive” (and in this dataset it is coded as citing “Article II authority”). But the report does cite both the 2001 AUMF and the WPR with respect to its “efforts to keep the Congress informed.” The ongoing operations stemming from that initial deployment over the last 18 years have largely been justified as authorized by the 2001 AUMF alongside the President’s constitutional authority.46 (President Obama’s two reports on September 23, 2014, involving operations against al-Qaida and ISIL in Iraq and Syria, also rely on the 2001 AUMF and constitutional authority.)

The reports noted in the paragraph above—involving the 1991 Gulf War, 2003 Iraq War, and post-9/11 counterterrorism operations—comprise four of the six reports that identify both Article II authority and congressional authorization for the activity at issue. The other two reports are President Ford’s reliance on the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, alongside “the President's constitutional authority as Commander-in-Chief and Chief Executive in the conduct of foreign relations” to conduct the Danang sealift in South Vietnam in the very first 48-hour report filed after the WPR’s enactment,47 and President Reagan’s deployment of U.S. forces to fulfill the U.S. obligation to the Multinational Force and Observers in the Sinai peninsula in order to ensure compliance with the 1979 peace treaty between Egypt and Israel—a mission that remains ongoing today.48

One could draw a conclusion that these reports show the WPR is working, at least in part, as intended. That is, the transparency-forcing function of 48-hour reporting combined with the pressure provided by the 60-day clock arguably have deterred Presidents from engaging in major wars without congressional authorization. However, that conclusion cannot be drawn based on this dataset alone, as there could be a host of other explanations for why Presidents have relied on statutory authority for major wars. There is also the possibility that Presidents have claimed a broad swath of activity is covered by the 2001 AUMF based at least in part on a desire to avoid the WPR’s 60-day clock for long-term counterterrorism operations in new theaters or against enemies beyond al-Qaida and the Taliban.

This dataset does, however, provide a mechanism for tracking whether military engagements that involve the initiation of long-term, large-scale uses of military force are undertaken with the support of both political branches or the President alone. To date, the data illustrate that since 1975, the “collective judgment of both the Congress and the President” have been applied at least in the initiation—if not the expansion—of these major conflicts.49

Presidents initiate involvement of U.S. armed forces in hostilities or imminent hostilities without congressional authorization, often stretching their claimed constitutional authority.

While the major wars noted above did involve congressional authorization, this dataset also illustrates how much additional reportable activity is undertaken outside of any statutory force authorization. Reliance on the President’s claimed constitutional authority alone is particularly striking with respect to the reports that involve hostilities or imminent hostilities (as opposed to combat-equipped deployments or substantial enlargements that may not involve imminent hostilities), given these are the situations that most clearly implicate Congress’ constitutional war powers.

Thirty-eight of the 105 reports in this dataset are categorized as having been triggered by the requirement to report the introduction of U.S. armed forces into hostilities or situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances. Of those, 34 rely on the President’s claimed Article II authority alone. (The other four reports are those relating to the initiation of major combat operations in large-scale conflicts, as discussed above.) These span every President but Carter, from the Ford Administration through the Trump Administration.

What is striking about these 34 reports is the number that involve hostilities or imminent hostilities but cite no statutory authority, and are undertaken for purposes that arguably lie beyond the long-recognized “core” of the President’s unilateral Article II authority: defending against sudden attack on the United States, and a limited set of related circumstances such as rescuing U.S. citizens.

In this dataset, presidential authority to repel sudden attacks roughly maps onto the “respond to threat” category—it is important to note, however, that the activity at issue in this category does not always indicate a sudden armed attack on the United States or imminent threat of such an attack, so even some of the activity in this category may be properly understood to lie beyond the President’s “core” Article II authority, at least as historically understood.50 Three derivatives of that implicit presidential authority include the following data categories: evacuations, rescues of U.S. nationals, and protecting U.S. embassies. In total, these four categories can be considered to constitute the core of the President’s unilateral authority to use U.S. armed forces abroad even in the absence of congressional authorization (although even this could be considered a generous representation of cases involving core Article II authority).

Seventeen of the 34 reports triggered by an introduction into hostilities or imminent involvement in hostilities both rely on the President’s Article II authority alone and notify Congress of missions that arguably fall outside of the core of that authority (again, at least as understood in historical perspective). These 17 reports, spanning Presidents Reagan, H.W. Bush, Clinton, Obama, and Trump through December 31, 2019 (but not W. Bush), show the stretching of claimed Article II authority to use armed forces abroad without congressional authorization in situations that extend well beyond core functions of repelling attacks and protection of U.S. nationals.

Notably, while the activities at issue rely on the President’s unilateral authority as a domestic law matter, almost all of them were undertaken in coalition with partner forces or organizations. This perhaps reflects that Presidents are willing to act on their own domestic authority—even when that authority is significantly stretched—when also acting with some degree of international support,51 or at least at the request of a partner nation. The exception is President Trump’s unilateral strikes against the Government of Syria in response to its use of chemical weapons in 2017, although his 2018 strikes in Syria were in coordination with two allies. Moreover, seven of the 17 reports describe activity that, though lacking in congressional authorization, was authorized by the UN Security Council as an international law matter, and a further six describe consent of the territorial state.

Regardless of their varying degrees of legitimacy on the international plane, these 17 reports provide a stark illustration of how the executive branch’s “national interests” test, described in the Introduction section above, does not appear to provide a meaningful constraint on unilateral presidential involvement of U.S. armed forces in hostilities or imminent hostilities.

48-Hour Reporting and the 60-Day Clock

Reports don’t identify whether the 60-day clock has started, and the WPR does not require that Congress receive information during the pendency of that period.

This research brings into sharp focus a key aspect of the WPR framework that is normally opaque—whether a given 48-hour report was filed because of an introduction of U.S. forces into hostilities or imminent involvement in hostilities, and in turn, whether the WPR’s termination clock (that requires Presidents to cease reported military activity if Congress has not authorized it after 60, or sometimes 90, days) has started.52 This dataset allows us to examine whether Congress has sufficient information about reported activity to determine whether the 60-day clock was triggered, whether the clock has stopped by the time of the notification (because the activity has ceased), or when the clock can be expected to expire based on the estimated “scope and duration” of the activity.

President Ford’s May 15, 1975, report regarding the rescue of the ship Mayaguez from the armed forces of Cambodia is the only report in the dataset that specifically names prong 4(a)(1) of the WPR. For another 37 reports, researchers determined that prong 4(a)(1) was triggered based on the text of the report as analyzed against interpretations of “hostilities” advanced by the executive branch.53 This enables a conclusion that 38 reports, submitted under section 4(a)(1), have started the 60-day termination clock.

Even assuming Congress can identify that a report is triggered by section 4(a)(1), how can it be determined whether the 60-day clock has stopped or continues to run following a 48-hour report? Under the WPR, no further reporting is required until six months after an initial 48-hour report is submitted—that is, a full four months after the 60-day clock would have run if reported hostilities were to have continued throughout that period. And that further reporting is required only under the periodic reporting requirement of section 4(c) for activities that remain ongoing.

This finding highlights the need for follow-on reporting during the pendency of the 60-day clock. While Congress could arguably use its oversight authority to request further information from the executive branch during that period, the lack of required reporting is a major omission in the WPR framework.

In practice, this issue is sometimes rendered moot before it needs to be resolved given the short duration of the activity at issue. Of the 38 reports coded as falling under section 4(a)(1), 17 are also coded to have had an actual duration of one to two days. In these short-duration cases, in which the activity is concluded before the 48-hour report is even filed, both the President and Congress avoid the issue of whether the clock started and, more important, whether the activity must be authorized or else terminated within 60 to 90 days. For the rest of these 38 reports, however, the actual duration of the activity was not known to Congress at the time the 48-hour report was filed.

The “estimated” duration provided in the initial 48-hour report is of little help in determining whether the President expects hostilities to continue: This dataset illuminates how vague the required reporting of the estimated duration of the activity tends to be, across administrations and regardless of the type of activity (the difficulty of meeting this reporting requirement is discussed further below). Of the 21 reports under section 4(a)(1) that were not coded as having a duration of only one to two days, the estimated duration was coded as “mission-bound” but unspecified in 19 cases (an often-proffered but ambiguous description that the activity will end whenever the mission is accomplished). In one report, the estimated duration was not provided at all. Thus, in all 20 cases, we know the 60-day clock started, but Congress does not necessarily know whether it ended, or even when the President believed it would end.

This is not to say that Congress never attempts to hold the executive branch to account if it believes the 60-day clock has started and the reported activity is ongoing. Indeed, the cases that have resulted in confrontations between the branches on this question—including operations authorized by President Clinton in Kosovo, by President Obama in Libya, and by President Trump in Yemen, to name a few—have shown a sharp division on whether activity that constitutes “hostilities” for WPR purposes remains ongoing. But there is no automaticity or uniformity to this oversight and it is not statutorily prescribed as part of the WPR framework.

The consistently vague reporting of estimated duration, combined with the initial difficulty in discerning whether the 60-day clock was triggered at all based on the text of a given 48-hour report and the narrow definition of “hostilities” employed by the executive branch, arguably prevent the crucial transparency the WPR is intended to provide. In sum, accountability for unilateral presidential deployments that exceed the WPR’s intended limitations is more likely to remain elusive without a common baseline understanding of whether hostilities commenced and whether they remain ongoing.

Two additional aspects of executive branch practice that hamper the clarity needed for the 60-day clock provisions to function as intended—first, the practice of starting and stopping the clock based on filing successive reports about related activity, and second, taking broad interpretations of existing statutory authority—are examined below.

Intermittence, Broad Interpretations of Statutory Authorization, and the 60-Day Clock

Several administrations have relied on starting and stopping of the 60-day clock through a theory of “intermittent” engagement in hostilities, and/or taken broad views of existing statutory authorization, in ways that sometimes appear intended to avoid expiration of the 60-day clock.

The dataset illustrates the much-discussed “intermittence theory,” in which the executive branch reports military engagements that could be seen to comprise ongoing hostilities as discrete events—potentially as an “end run” around the 60-day termination clock. The best example of this practice is during the “Tanker War” of the late 1980s, which involved the U.S. re-flagging Kuwaiti vessels exporting oil through the Persian Gulf during the Iran-Iraq War. President Reagan sent U.S. naval forces to the region to protect these and other commercial vessels from attack by Iran, triggering a series of military engagements. As former senior State Department official Todd Buchwald explains:

During the tanker war, there were several particular military incidents that began at least as early as the Iraqi attack on the USS Stark in May 1987, and included incidents involving Iranian attacks between September 1987 and July 1988, that were easily characterized as involvement in actual hostilities, as opposed to imminent hostilities. Following some early incidents in which reports were not submitted to Congress, the Reagan Administration fell into a familiar pattern of reporting incidents to Congress, saying it was doing so “consistent with the War Powers Resolution” but taking no formal position on whether it considered that US forces had been introduced into hostilities — actual or imminent. This position allowed it to maintain at least some nominal level of uncertainty about whether the 60-day clock had been triggered. . . . But even on the premise that U.S. forces had been introduced into hostilities and that the clock had been triggered, the Reagan Administration treated these incidents as discrete – as if each started its own 60-day period.

This series of military engagements (several of which involved casualties) was reported as six distinct events spanning from September 24, 1987, to July 14, 1988—a period that is of course much longer than 60 or 90 days. The first three reports in this series simply noted the dates of the activity, and all occurred well within a 60-day window (from the first report in the series to a report on October 20, 1987). The last three, however, occurred outside of that window. Each of those last three reports states, “we regard this incident as closed” or something similar, indicating the intent to “stop” the clock. Any additional hostilities reported would, on this view, constitute a new incident that would trigger a new 60-day window for military engagement.54

The use of armed forces in Somalia spanning the administrations of President H.W. Bush and Clinton (first reported on December 10, 1992) also controversially lasted far longer than 60 days, including sporadic fighting that incurred U.S. casualties. In that context, the Clinton Administration in 1993 argued that “intermittent” military engagements would not necessitate withdrawal under the WPR because the 60-day clock was intended to apply to “sustained” hostilities. The so-called “intermittence” theory may also have been in play during a series of reports by President Clinton in the 1990s involving air operations in the former Yugoslavia.55

More recently, some argue an “end run” around the 60-day clock was evident in President Obama’s reports of discrete operations in Iraq beginning during the summer of 2014. On August 8, 2014, President Obama notified Congress of “targeted airstrikes” to stop the “advance on Erbil by the terrorist group Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and to help forces in Iraq as they fight to break the siege of Mount Sinjar and protect the civilians trapped there.”56 Five additional reports followed in quick succession, the last of which, on September 23, 2014, announced implementation of a “new comprehensive and sustained counterterrorism strategy to degrade, and ultimately defeat, ISIL.”57 Still well within the 60-day window, this final report switched tacks by arguing that the operations were authorized by the 2001 AUMF—a controversial interpretation of the statute. Nevertheless, this assertion took the wind out of the sails of the argument that the 60-day clock would expire on October 8 and require withdrawal of U.S. forces from counter-ISIL operations in Iraq.

It remains a matter of debate whether this cluster of reports consistently updating Congress on new developments over a period of a few months shows the WPR working as intended or, perversely, shows that it incentivized the executive branch to stake out an overly broad interpretation of an existing statutory force authorization to avoid expiration of the WPR’s 60-day termination clock. This potential perverse incentive merits close attention in discussions of WPR reform.

Sufficiency of Reporting: Does WPR Reporting Provide Congress the Required Information?

Most reports attempt to fulfill all three informational requirements, although the “estimated scope and duration” of reported activity often fails to provide meaningful information.

Have Presidents provided Congress with the information the WPR requires? Section 4(a) of the WPR requires that the President submit, “in writing,” the following three types of information in 48-hour reports: “(A) the circumstances necessitating the introduction of United States Armed Forces; (B) the constitutional and legislative authority under which such introduction took place; and (C) the estimated scope and duration of the hostilities or involvement.”58

The first requirement to report the circumstances necessitating introduction, categorized in this dataset as the “stated purpose or mission,” is arguably the easiest to satisfy, in part because the statutory requirement itself is stated in broad terms. This dataset shows that it is almost always reported in a manner that is sufficient to understand the general circumstances at issue, albeit often without a great deal of specificity. Only one report in the dataset was categorized as “other.”59 The “constitutional and legislative authority” is also almost always reported sufficiently: A failure to report the domestic authority under which an introduction took place was identified in only two cases.60

The third required type of information—the estimated scope and duration of the hostilities or involvement—is the least meaningfully reported. Eight reports were coded as failing to provide an estimated duration at all (one of which involves hostilities or imminent involvement in hostilities). When taking into account the unstructured data in this category, however, the distinction between providing no estimated scope and duration at all and including some mention of this statutorily required prong is relatively small; even where estimations are provided, they often are not detailed enough to meaningfully inform Congress of when the activity should be expected to cease.

It should be underscored that it can be genuinely difficult to meet the statutory requirement of reporting an estimated duration of an activity within 48 hours of its commencing. Based on the reports analyzed in this dataset, it appears the executive branch believes the duration of an introduction or deployment can often be reported with a reasonable degree of certainty only when the operation at issue has already concluded before the report is submitted—examples include certain hostage rescues or evacuations that can be completed within 48 hours, or isolated hostilities (such as targeted airstrikes). There are 29 reports in the dataset that do provide a specific, estimated duration, but 24 of these are cases in which the actual duration of the activity was shorter than the 48-hour reporting period (that is, only five reports attempt to estimate a specific duration beyond the one to two day reporting period itself).

Outside of these situations, Presidents are often reluctant to provide a specific estimation of the duration of activity at the outset of a deployment. Instead, Presidents often report that “although it is not possible at this time to predict the precise duration”61 of the activity, it will end when the mission is accomplished or the risk at issue is no longer present.62 Well over half of the reports in this dataset (68) were coded as “mission-bound but unspecified” in the “estimated duration” category based on language similar to this.

While perhaps an accurate description of the state of knowledge within the executive branch at the time of reporting, and while arguably facially responsive to the statutory requirement, this type of response does not give Congress meaningful information that could help it determine whether a long-term entanglement is likely. As noted above, it also does not allow Congress to track whether the activity at issue is expected to cease during the pendency of the 60-day clock if it has been triggered, particularly given that follow-on reporting is not required for another four months after the clock would terminate.

Finally, the executive branch may not want to offer more detailed information than is strictly required by the WPR’s reporting requirements, so as to avoid setting a precedent of providing more robust information in cases for which it believes doing so would be problematic (for any number of reasons ranging from actual uncertainty, to a need to maintain the classification of operational details, to a desire to avoid additional congressional scrutiny). The incentive not to “over-report,” in the executive branch’s view, may also be at issue with respect to the other required reporting categories, and is an additional issue that merits consideration in proposals for WPR reform.

The International Legal Basis of Reported Activity

While not required by the WPR’s text, over half of the reports nevertheless provide information on the international legal basis for the reported activity.

Sixty-one of the 105 reports provide sufficient information to determine the claimed international legal basis for the activity at issue, even though this information is not statutorily required in 48-hour reports. The reports span every administration from Ford to Obama (the Trump Administration is the outlier) and include missions of every type coded in this dataset. Twenty-four report authorization by the UN Security Council; 21 provide information indicating the consent of the territorial state; and 18 assert self-defense (for 16 of these, researchers were able to verify communications to the United Nations under Article 51 of the UN Charter).

It is particularly noteworthy that Presidents seem more likely to provide information on the international legal basis for the reported activity when it involves hostilities. Out of the 38 reports coded as falling under section 4(a)(1) (reporting hostilities or imminent involvement in hostilities), 30 provide information indicating an international legal basis for the activity, whereas only 31 out of the 67 reports not triggered by 4(a)(1) provide this information. While it is not possible to discern why this is the case from this data alone, it is possible that Presidents feel more compelled to justify the international legal basis of their actions when using force or directing operations that could proximately lead to the use of force, which is often the case for introduction of U.S. armed forces into hostilities and is not necessarily the case for the other two triggers (combat-equipped introductions and substantial enlargements thereof).

Unreported Activity

Unreported activity illustrates instances of inconsistent reporting by the executive branch and the limitations of the WPR framework, especially in light of modern military practice.

As described in greater length in the methodology section, researchers also coded a set of U.S. military activity abroad that was not detailed in 48-hour reports to Congress, as compiled by the Congressional Research Service. The vast majority of the activity in this sample appears to be unreported not because of a failure to report on the part of the President, but because it did not trigger any of the WPR’s 48-hour report prongs, at least in the view of the executive branch. For example, a deployment of non-combat equipped troops for a disaster-relief mission in which no hostilities or imminent involvement in hostilities are anticipated would not trigger any of the reporting prongs in section 4(a) of the WPR statute.

There are also some types of operations that the WPR did not contemplate when drafted in 1973 and thus escape its reporting requirements, as described above. A paradigm example is an operation conducted remotely without “introduction” of combat-equipped forces and without any appreciable risk to U.S. forces, such that the executive branch’s definition of “hostilities” is not met. A hostile cyber operation conducted remotely would fit this description, for example, and to date no known 48-hour reports exist regarding such operations.

It is worth noting that even with respect to more conventional uses of force remotely, such as “over-the-horizon” missile strikes launched from international waters, some of this kind of activity has been reported as hostilities, while other similar activity has not. As an example of this inconsistent practice, the Reagan Administration failed to report the shoot-down of Libyan jets in 1981 and 1989, even though it reported a similar incident in 1986.63

Unreported activity can also create precedents within the executive branch for when WPR reporting is not required. For example, the unreported data sample includes an incident involving the use of U.S. surveillance aircraft to aid in the shoot-down of Iranian planes by Saudi Arabia in June 1984, which was not notified to Congress in a 48-hour report and which arguably set a precedent for not reporting advise and assist missions when a partner force takes direct kinetic action enabled by U.S. support.

The unreported data sample also shows the extent to which the U.S. military footprint abroad is greater than that represented by WPR-reported activity alone. It provides a window into the breadth of activities armed forces are deployed to undertake, ranging from Ebola outbreak assistance in Liberia and Senegal, to assisting in raids against drug traffickers in Bolivia. And because it includes activity from periodic reports under section 4(c) of the WPR, it illustrates in some cases the scope of WPR-reported activity expanding over time, such as the U.S. missions in Afghanistan and Iraq, which remain ongoing today.

In addition, the sample of unreported activity shows a number of ways in which the existing WPR framework may be insufficient to inform Congress of military activity that risks entangling the United States in conflict or raises the prospect of significant geopolitical consequences. As an example, the unreported sample includes advise and assist missions in Central America in the 1980s that arguably did not trigger 48-hour WPR reporting requirements because U.S. armed forces held back from areas where hostilities were likely to occur, and were not “combat-equipped.”64 Similarly, the provision of refueling capability to Saudi air operations and other U.S. military support in the conflict in Yemen during the Obama and Trump Administrations is another case in which the activity at issue was not deemed reportable, despite the risk of drawing the United States into a long-running conflict with enormous strategic and humanitarian ramifications.65 These examples highlight the consequences of the executive branch’s narrow interpretations of the WPR’s key terms “hostilities” and “combat-equipped.”

Conclusions

The above analysis only scratches the surface of what can be gleaned from the War Powers Resolution Reporting Project’s 48-hour report database. Nevertheless, these findings begin to illustrate significant trends in how Presidents are using U.S. armed forces abroad. The analysis shows, for example, the specific ways in which claimed presidential authority to use U.S. forces abroad without congressional authorization has expanded over recent decades to include missions that the executive branch deems in the “national interest” but that reach beyond the traditionally understood core of the President’s unilateral Article II authority.

The analysis also shows trends in WPR-reporting practice that shed light on areas for potential reform. First, it illuminates significant gaps in the WPR’s reporting framework. The failure to require Presidents to specify which prong triggered the requirement to submit a 48-hour report and the failure to require follow-on reports during the pendency of the 60-day termination clock period are two of the most prominent examples. Of course, other information that Presidents sometimes but not always report could also be placed in the category of information that should be required—such as the international legal basis of the operations, whether any casualties of U.S. or non-U.S. persons have occurred or are expected, and whether the United States is acting alone or in a coalition with partner nations or organizations.66 The fact that Presidents often feel motivated to include these categories of information may well reveal their relevance and utility.

Second, this analysis also shows deficiencies in practice by the executive branch, even where the WPR framework already calls for more robust reporting by the President. For example, the high level of generality with which the estimated scope and duration are generally expressed could undermine Congress’ ability to gain a meaningful understanding of the reported activity. The absence of this information is even more concerning since the Department of Defense generally calculates those very contingencies, and thus should have more specific information than Congress receives. The counterargument, of course, is that Congress may, in the exercise of its oversight authority, seek whatever additional information is needed. However, such exercises of oversight are difficult to initiate in Congress, can take more time, and the requested information would not be based on a statutory reporting obligation.

This dataset has also shown ways in which the WPR is generally working as intended. For example, it shows that Presidents have for the most part provided Congress with the information required by the WPR, albeit with some important gaps and ambiguities in reporting. Moreover, they have often provided additional information that is not strictly required by the terms of the statute, but creates greater transparency and an opportunity for meaningful oversight, such as the international legal basis for operations and whether they are undertaken in coalition with other states or organizations.

In addition, the WPR appears to have succeeded in ensuring that Congress receives information within 48 hours of new combat-equipped deployments (or substantial enlargements of those deployments), including whether those deployments are undertaken without statutory authority. This information should help Congress to determine whether a given deployment risks involving the United States in a situation with political, humanitarian, or strategic consequences at odds with its foreign policy aims, or conversely, whether such activity should be supported by the legislative branch. And as discussed above, this dataset also shows that Presidents have, since the WPR’s enactment, engaged in major, long-term conflicts in reliance on both statutory authority and Article II authority, rather than on claimed unilateral constitutional authority alone.

The key findings described here represent only some of the conclusions that can be drawn from the project data, and there are undoubtedly many avenues for future research and ways to expand the dataset for further analysis. As U.S. military engagement abroad remains expansive in the scope and duration of deployments, this living project will provide a resource for understanding presidential action, identifying means of strengthening congressional oversight, and exploring ways in which the balance of war powers can be calibrated for the future.

The Findings & Analysis are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License.

See U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 1 (“The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.”). Congress’ war powers are enumerated in Article I. See U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 11 (authority to declare war, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and make rules governing capture on land and water); id cl. 12 (authority to fund military operations); id cl. 13 (authority to provide and maintain a navy); id cl. 14 (authority to make rules regulating land and naval forces); id. cl. 15, 16 (authority relating to raising and providing for militias); id. cl. 18 (authority to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States”).

Brian Egan & Tess Bridgeman, Top Experts’ Backgrounder: Military Action Against Iran and US Domestic Law, Just Security (June 21, 2019), https://www.justsecurity.org/64645/top-experts-backgrounder-military-action-against-iran-and-us-domestic-law. Scholar John Hart Ely explained this decision as “a determination not to let such decisions be taken easily,” or for unpopular purposes. John Hart Ely, War and Responsibility: Constitutional Lessons of Vietnam and Its Aftermath 3–4 (1993) (“The founders didn’t need a Vietnam to teach them that wars unsupported by the people at large are unlikely to succeed.”). And Professor David Golove notes that this feature ensures the elected officials closest to the people have an opportunity for meaningful consideration—the House of Representatives, in particular, “had a vital role to play in restraining military conflict.” David Golove, The American Founding and Global Justice: Hamiltonian and Jeffersonian Approaches, 57 Va. J. Int’l L. 621, 625 (2018) (“The people, [the Founders] imagined, were pacifistic and would resist wars and the human suffering and taxes that military ventures inevitably produced.”).

For a concise overview of the historical position on the President’s authority to initiate the use of force without congressional authorization, the contemporaneous test, and a maximalist position expressed during the W. Bush Administration, see Marty Lederman, Syria Insta-Symposium: Marty Lederman Part I–The Constitution, the Charter, and Their Intersection, Opinio Juris, (Jan. 9, 2013), http://opiniojuris.org/2013/09/01/syria-insta-symposium-marty-lederman-part-constitution-charter-intersection.

Tess Bridgeman & Stephen Pomper, Introduction: The War Powers Resolution, Tex. Nat’l Security Rev.: Pol’y Roundtable (Nov. 14, 2019), https://tnsr.org/roundtable/policy-roundtable-the-war-powers-resolution/#intro; see also Curtis Bradley & Jack Goldsmith, OLC’s Meaningless ‘National Interests’ Test for the Legality of Presidential Uses of Force, Lawfare (June 5, 2018), https://www.lawfareblog.com/olcs-meaningless-national-interests-test-legality-presidential-uses-force.

Bridgeman & Pomper, supra note 4. As former senior State Department official Todd Buchwald has described it:

[T]he two-pronged test that the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) has articulated is remarkably elastic and easily satisfied. . . . On its face, the first prong would only bar cases in which it could be shown that the President was unreasonable in concluding that a use of force was in the national interest. The debate about the reasonableness of any such determination is well worth having but is on its face political in nature. The second prong depends on “the anticipated nature, scope, and duration of the operations [being] sufficiently limited,” but “anticipated” is a funny word. Different actors will doubtless anticipate different outcomes.

Todd Buchwald, Anticipating the President’s Way Around the War Powers Resolution on Iran: Lessons of the 1980s Tanker Wars, Just Security (June 28, 2019), https://www.justsecurity.org/64732/anticipating-the-presidents-way-around-the-war-powers-resolution-on-iran-lessons-of-the-1980s-tanker-wars.

At the time of the WPR’s passage, “[m]ost Members of Congress agreed that the President as Commander in Chief had power to lead the U.S. forces once the decision to wage war had been made, to defend the nation against attack, and perhaps in some instances to take other action such as rescuing American citizens.” Matthew C. Weed, Cong. Research Serv., R42699, The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice 7 (2019).

See April 2018 Airstrikes Against Syrian Chemical-Weapons Facilities, 42 Op. O.L.C. slip op. at 9 (2018), https://www.justice.gov/olc/opinion/file/1067551/download; see also Deployment of United States Armed Forces into Haiti, 18 Op. O.L.C. 173, 173, 177–79 (1994), https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/olc/opinions/1994/09/31/op-olc-v018-p0173.pdf. The executive branch has recognized that use of force against state actors (as opposed to within the territory of another state with its consent), or where there is a high likelihood of escalation, are more likely to meet this test.

War Powers Resolution, Pub. L. No. 93-148, 87 Stat. 555 (1973).

The WPR’s stated purpose is “to fulfill the intent of the framers of the Constitution of the United States and insure that the collective judgment of both the Congress and the President will apply to the introduction of United States Armed Forces into hostilities [or] situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances…” Id. § 2(a). In contrast to the contemporary view expressed by the executive branch, the WPR provides that the President has authority to introduce U.S. armed forces into hostilities, or situations where involvement in hostilities is imminent, “only pursuant to (1) a declaration of war, (2) specific statutory authorization, or (3) a national emergency created by an attack upon the United States, its territories or possessions, or its armed forces.” Id. § 2(c).

Section 3 of the WPR, which requires the President to consult Congress before introducing forces into “hostilities” or “situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances,” is also intended to ensure congressional knowledge and input prior to engagements of U.S. armed forces abroad. Id. § 3.

Id. § 4(a). The limited exceptions for reporting combat-equipped deployments are for those “which relate solely to supply, replacement, repair, or training of such forces.” Id. § 4(a)(2).

All reports under section 4(a) are required to provide, in writing: “(A) the circumstances necessitating the introduction of United States Armed Forces; (B) the constitutional and legislative authority under which such introduction took place; and (C) the estimated scope and duration of the hostilities or involvement.” Id. § 4(a). The legislative history makes clear that the WPR’s reporting provisions are intended to “ensure that the Congress by right and as a matter of law will be provided with all the information it requires to carry out its constitutional responsibilities with respect to committing the Nation to war and to the use of United States Armed Forces abroad.” H.R. Rep. No. 93-547, at 8 (1973) (Conf. Rep.).

Section 5(b) of the WPR provides that 60 days after a report under section 4(a)(1) is “required to be submitted,” the President “shall terminate any use of United States Armed Forces with respect to which such report was submitted (or required to be submitted)” unless Congress has authorized such use of U.S. Armed Forces during that period. War Powers Resolution § 5(b). Termination is not required, however, if Congress has extended the period “by law” or “is physically unable to meet as a result of an armed attack on the United States.” Id. The 60-day period may be extended to “not more than” 90 days if the President “certifies to the Congress in writing that unavoidable military necessity respecting the safety of United States Armed Forces requires the continued use of such armed forces in the course of bringing about a prompt removal of such forces.” Id. A separate provision, section 5(c), requires the President to remove armed forces “engaged in hostilities” outside the United States at any time “if the Congress so directs by concurrent resolution.” Id. § 5(c). This provision was subsequently gutted by an unrelated Supreme Court decision. See infra note 16.

In 1975, the Ford Administration described “hostilities” as “a situation in which units of U.S. armed forces are actively engaged in exchanges of fire with opposing units of hostile forces.” Letter from Monroe Leigh, Legal Adviser, U.S. Dep’t of State, and Martin R. Hoffman, Gen. Counsel, U.S. Dep’t of Def., to Hon. Clement J. Zablocki, Chairman, Subcomm. on Int’l Sec. and Sci. Affairs, Comm. on Int’l Relations, U.S. House of Representatives (June 3, 1975), in War Powers: A Test of Compliance: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Int’l Sec. and Sci. Affairs of the House Comm. on Int’l Relations, 94th Cong. 38–40 (1975). See generally Libya and War Powers: Hearing Before the S. Foreign Relations Comm., 112th Cong. (2011) [hereinafter Koh Hearing] (statement of Harold Hongju Koh, Legal Adviser, U.S. Dep’t of State), https://2009-2017.state.gov/s/l/releases/remarks/167250.htm (arguing that historical practice suggests that situations in which the nature of the mission, exposure of U.S. armed forces, risk of escalation, and military means are limited do not constitute “hostilities” that trigger the WPR’s 60-day automatic pullout provision); Deployment of United States Armed Forces to Haiti, 28 Op. O.L.C. 30, 34 (2004), https://www.justice.gov/file/18876/download (“Although it is also possible that some level of violence and instability will continue, we previously have concluded that ‘the term “hostilities” should not be read necessarily to include sporadic military or paramilitary attacks on our armed forces.’” (quoting Presidential Power to Use Armed Forces Abroad Without Statutory Authorization, 4A Op. O.L.C. 185, 194 (1980))); Overview of the War Powers Resolution, 8 Op. O.L.C. 271, 275 (1984), https://www.justice.gov/file/23691/download (“The Ford Administration took the position that ‘hostilities’ meant a situation in which units of our armed forces are ‘actively engaged in exchanges of fire’” and “‘imminent hostilities’ meant a situation in which there is a ‘serious risk’ from hostile fire to the safety of United States Armed Forces. ‘In our view, neither term necessarily encompasses irregular or infrequent violence which may occur in a particular area.’” (citing War Powers: A Test of Compliance, supra)).

See Letter from Richard Nixon, President of the U.S., to the House of Representatives on Veto of the War Powers Resolution (Oct. 24, 1973) (arguing that the termination provision is unconstitutional because it “would allow the Congress to eliminate certain authorities merely by the passage of a concurrent resolution—an action which does not normally have the force of law, since it denies the President his constitutional role in approving legislation”).

See Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983). As Bridgeman and Pomper explain, the decision, “by invalidating the ‘legislative veto,’ casts essentially fatal doubt on Congress’ ability to order the withdrawal of U.S. forces by concurrent resolution. Following Chadha, in the face of presidential resistance, Congress can only enforce withdrawal if it commands a veto-proof supermajority. The Supreme Court’s decision also encouraged a lingering (and in our view incorrect) impression that other provisions of the War Powers Resolution are constitutionally infirm — an impression that the executive branch has sometimes encouraged.” Bridgeman and Pomper, supra note 4.

See Nixon, supra note 15 (stating that the WPR “would attempt to take away, by a mere legislative act, authorities which the President has properly exercised under the Constitution for almost 200 years. One of its provisions would automatically cut off certain authorities after sixty days unless the Congress extended them” and arguing that this provision is “unconstitutional”).

Presidential Power to Use the Armed Forces Abroad Without Statutory Authorization, 4A Op. O.L.C. at 196; see also Koh Hearing, supra note 14 (“The Administration recognizes that Congress has powers to regulate and terminate uses of force, and that the War Powers Resolution plays an important role in promoting interbranch dialogue and deliberation on these critical matters.”); Authorization for Continuing Hostilities in Kosovo, 24 Op. O.L.C. 327 (2000), https://www.justice.gov/file/19306/download.

As a 1979 O.L.C. opinion explains, “When President Nixon vetoed the Resolution he did not suggest that either the reporting or consultation requirements were unconstitutional. Neither the Ford nor Carter administrations have taken the position that these requirements are unconstitutional on their face.” Supplementary Discussion of the President’s Powers Relating to the Seizure of the American Embassy in Iran, 4A Op. O.L.C. 123, 128 (1979), https://www.justice.gov/olc/file/476871/download. It then explains that “[t]he only provision that this Administration has suggested presents constitutional problems related to the right of Congress to act by concurrent resolution,” while noting some potential applications in which the consultation requirements—but not the reporting requirements—could “raise constitutional questions.” Id. at 128–29, 128 n.4 (internal citations omitted). It should be noted that Presidents often state they are providing reports “consistent with” the WPR, rather than “pursuant to” its requirements, in what could be seen as an attempt to preserve an argument that the reporting may not be required. However, this has not been a meaningful distinction in practice and the reporting requirements have not in fact been contested.

Donald J. Trump, Deployment of U.S. Armed Forces to Saudi Arabia, H.R. Doc. No. 116-82 (Nov. 19, 2019).

President W. Bush also only filed eight reports in his first term, but two of them reported the beginning of major combat operations in large-scale, long-term armed conflicts—the conflict against al-Qaida and the Taliban in Afghanistan that quickly metastasized into the “Global War on Terror,” and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. See George W. Bush, Report on Military Actions Taken to Respond to the Threat of Terrorism, H.R. Doc. No. 107-131 (Oct. 9, 2001); George W. Bush, A Report Consistent with the War Powers Resolution Regarding the Use of Military Force Against Iraq, H.R. Doc. No. 108-54 (Mar. 21, 2003).

Note that this adds up to more than 105 because some reports were coded as having more than one trigger under section 4(a) of the WPR.

For example, President H.W. Bush reported on August 6, 1990, a deployment to “provide additional security at the U.S. Embassy in Monrovia, Liberia” and “extract American citizens . . . . and a limited number of foreign nationals,” and stated that the mission is “not intended to alter or preserve the existing political status quo or to make the U.S. presence felt in any way.” See Letter from George H.W. Bush, President of the U.S., to Congressional Leaders on the Use of United States Armed Forces in Liberia (Aug. 6, 1990) (emphasis added). Similarly, President Clinton reported on March 27, 1997, deployment of a “standby evacuation force” to provide security for U.S. citizens and “selected third country nationals” in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire), and stated that “this movement is being undertaken solely for the purpose of preparing to protect American citizens and property.” See Letter from William J. Clinton, President of the U.S., to Congressional Leaders on the Situation in Zaire (Mar. 27, 1997) (emphasis added).

Only one report was categorized as “other”—President Obama’s report on October 14, 2015, which stated the purpose of a combat-equipped introduction of forces into Chad only as “to conduct airborne intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance operations in the region.” See Letter from Barack Obama, President of the U.S., to Congressional Leaders on the Deployment of United States Armed Forces Personnel to Cameroon (Oct. 14, 2015).

The only outlier is the Obama Administration’s October 14, 2016, report notifying Congress of air strikes “in response to anti-ship cruise missile launches perpetrated by Houthi insurgents that threatened U.S. Navy warships in the international waters of the Red Sea.” Letter from Barack Obama, President of the U.S., to Congressional Leaders on the War Powers Resolution Report for Yemen (Oct. 14, 2016).

Whether all of this activity should properly be understood as falling under the 2001 AUMF remains a matter of debate.

The January 18, 1991, report states that combat operations to “compel Iraq to withdraw unconditionally from Kuwait and meet the other requirements of the U.N. Security Council and the world community” were taken both “pursuant to my authority as Commander in Chief” and as “contemplated by . . . H.J. Res. 77, adopted by Congress on January 12, 1991.” Letter from George H.W. Bush, President of the U.S., to Congressional Leaders on the Persian Gulf Conflict (Jan. 18, 1991).

The March 21, 2003, report states that “combat operations . . . against Iraq” were undertaken “pursuant to my authority as Commander in Chief and consistent with the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution (Public Law 102–1) and the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 (Public Law 107–243).” George W. Bush, A Report Consistent with the War Powers Resolution Regarding the Use of Military Force Against Iraq, H.R. Doc. No. 108-54 (Mar. 21, 2003).

While it does not explicitly claim the 2001 AUMF as a source of authority for the reported operations, President W. Bush’s Sept. 24, 2001, report subsequently notes the 2001 AUMF, alongside the WPR, as follows:

I am providing this report as part of my efforts to keep the Congress informed, consistent with the War Powers Resolution and Senate Joint Resolution 23, which I signed on September 18, 2001. As you know, officials of my Administration and I have been regularly communicating with the leadership and other Members of Congress about the actions we are taking to respond to the threat of terrorism and we will continue to do so. I appreciate the continuing support of the Congress, including its passage of Senate Joint Resolution 23, in this action to protect the security of the United States of America and its citizens, civilian and military, here and abroad.

President Reagan’s March 19, 1982, report states: “The deployment of U.S. forces to the Sinai for this purpose is being undertaken pursuant to Public Law 97-132 of December 29, 1981, and pursuant to the President’s constitutional authority with respect to the conduct of foreign relations and as Commander-in-Chief of U.S. Armed Forces.” Letter from Ronald Reagan, President of the U.S., to Congressional Leaders on United States Participation in the Multinational Force and Observers (Mar. 19, 1982).

One of the stated purposes of the WPR is “to fulfill the intent of the framers of the Constitution of the United States and insure that the collective judgement of both the Congress and the President will apply to the introduction of United States Armed Forces into hostilities . . . .” War Powers Resolution, Pub. L. No. 93-148, § 2(a), 87 Stat. 555, 555 (1973).

For example, the invasion of Iraq in 2003 arguably was not a response to an imminent threat of attack against the United States.

Some forms of international support, most notably a strong UN Security Council mandate, can also be seen as bolstering domestic legal authority for presidential action.

Under the WPR, the 60-day clock is only triggered by an introduction into hostilities or imminent involvement in hostilities that is clearly indicated by the circumstances. See War Powers Resolution § 4(a)(1); see also supra note 13.

See supra note 14.

Note that this dataset records each of these six instances as triggered by section 4(a)(1).

Marty Lederman, for example, argues:

It is possible, but uncertain, that a similar interpretation was at work with respect to the deployment of U.S. aircraft to Bosnia in support of a NATO-enforced “no-fly” zone in 1994. In that case, President Clinton reported to Congress in March and April 1994 that U.S. forces had fired against Serbian forces. There was no withdrawal of U.S. forces 60 days after either WPR report; and then in August and again in November of that year, President Clinton filed separate WPR reports of additional U.S. strikes against Serbian forces, thereby suggesting (without stating) that the Administration might have concluded that “hostilities” and a “clear indication” of “imminent hostilities” had perhaps terminated sometime after each discrete operation, and that a new 60-day clock began running upon each resumption of active engagement with or against the Serbs.